Happy August 1st!

Lughnasadh is the grain harvest. Wheat, corn, barley, oats etc are ready to be harvested between now and Mabon, the Autumnal Equinox. The days slowly grow longer, plants begin to go to seed. All of my herbs are eager to create small blossoms. Bees happily take advantage of this opportunity to dance across innumerable tiny blooms, pollinating as they collect nutrients for their winter slumber.

Once again my work is too long for email. If you want to read the whole article please click on the title or ‘open in browser.’

Last week I wrote about an article that I read about standing out in a market. A lot of it is true; however, I am dissatisfied with what I wrote, because a part of me knew that this was just an excuse to not meet my own expectations in other skills.

Expertise is important, and people will acknowledge others with high skill, but if they never learn who you are nor experience your work then does that acknowledgement matter?

Indigo!

Indigo is a beautiful weed that has been harvested, transplanted, and adapted to various regions all across the world. Indigofera Tinctoria (Indian Indigo), Persecaria Japonica / Polygonium Tinctorum (Japanese Indigo), Indigofera suffruticosa (American Indigo), Indigofera arrecta, Isatis tinctoria (woad), and Istatis Indigotica (Chinese woad). For eons humans have cultivated and appreciated the beauty of indigo plants and their colour.

Indigo blue is a fascinating colour that has captured the interest of humanity. The plant family creates a variety of colours. The most famous of which is deep indigo blue. That navy that kisses midnight tones, nearing black in its depth. During the era of plant based dyes, indigo reined as one of the most light fast, wash fast colours. It still holds that title today in the use of synthetic indigo made from tar (instead of purely plant based indigo).

My friend Salamander Studios is hosting a workshop at a kids camp in late August and asked about uses for her indigo plants. I have done a fair bit of research into growing and using fresh leaf indigo dyes, and wrote an article for Digits and Threads.1 After many experiments with dying cloth in indigo vats and baths, let’s review their properties.

Is it really a weed?

Yes, Indigo has been a weed-type plant (like it’s some kind of Pokémon) for eons. Probably since it was first discovered, which is why it’s so useful. It’s a fast growing, sun loving, relatively resilient plant. They can be cut back by half and continue growing without any shock. If it is spaced out then it will grow more leaves from each node to maximize sunlight exposure. It produces numerous blossoms and from those blossoms come numerous seeds. The nodes of the plant can be tucked against soil, and roots will swiftly emerge to anchor the plant.

Herbs could be considered weeds, too, if they weren’t so delicious.

There are lots of ways to use your indigo plants. Many people think that the main way to use indigo is to reduce the indigo plant into patties of indigo blue, and then create a vat. There are various methods to create a vat using indigo powder and we won’t be touching on all of them. This takes up to half a year of aeration and reduction of the pigments from the plants. There is the aerating water bath method from India and the sukumo technique from Japan (among many other techniques). For all their efforts a person will have reduced indigo pigment of lesser quality than what would be manufactured and sold by a supplier such as Maiwa. This would then be introduced to a vat where it can become soluble and penetrate cloth.

Science time:

The word “Indigo” encapsulates the dying process, the colour, and the pigment. When we think about indigo we are recalling the deep saturated colour of the pigment, an insoluble compound called Indigotin.

John Marshall speaks clearly on the chemical interaction in his book Singing The Blues: “Indican is contained in the leaves of indigo plants. It combines in solution with enzymes to indoxyl. Indoxyl combines with oxygen to product indigotin.”

In pottery, when an kiln environment is starved of oxygen it is called a “reduction firing.” In this oxygen-less environment all sorts of unique reactions can occur that create effects unique to that environment. Copper red, carbon bonding, and the cool glass of true high fire celadon are some effects.

In indigo dying techniques, we use the reduction atmosphere created inside of the vat to break indoxyl’s bond with oxygen, disable the enzyme, and free indican. This is observed as leucoindigo aka “white indigo” in the vat (it actually appears yellow-yellow-green). Once more in a soluble state, the indican can flow inside of our cloth, where it is then lifted into an oxygen rich atmosphere that proceeds to bind the indican into indoxyl then indigotin inside of the fibre.

Fermentation can also create an environment similar to a reduction environment, called an ‘anaerobic’ (without air) environment.

Next option is the fermentation vat. This takes less time than the previous method, and can use fresh leaves or reduced pigment. The leaves will have less consistent amounts of indigotin, but will use the entire leaf as a fuel source for reduction. It involves sources of starches and sugars to create the reduction atmosphere, and soda ash to modify the pH. This takes a week or so, as Catherine Ellis details in a series of blog posts. Here is the recipe that Ellis uses, and it claims that the fermentation takes about a week.2

Both of these processes result in a “vat,” a reduction atmosphere with alkaline pH that allows the indigotin to turn from an insoluble pigment into a soluble pigment. These are great for dying large amounts of cloth, both cellulose and protein fibres (under certain circumstances), resisting areas with Shibori or Nori Paste, and with the appropriate care can be kept around for several months or years.

What if there was a more immediate process to be used with the leaves?

All of the following processes can be attempted on cellulose and protein fibres, but I have found that the most effective results are on protein fibres (wool and silk). Every process below must be used as swiftly as possible. Once the leaves or even stems are cut from the plant the indican begins to oxidize, lowering the concentration of pigment.

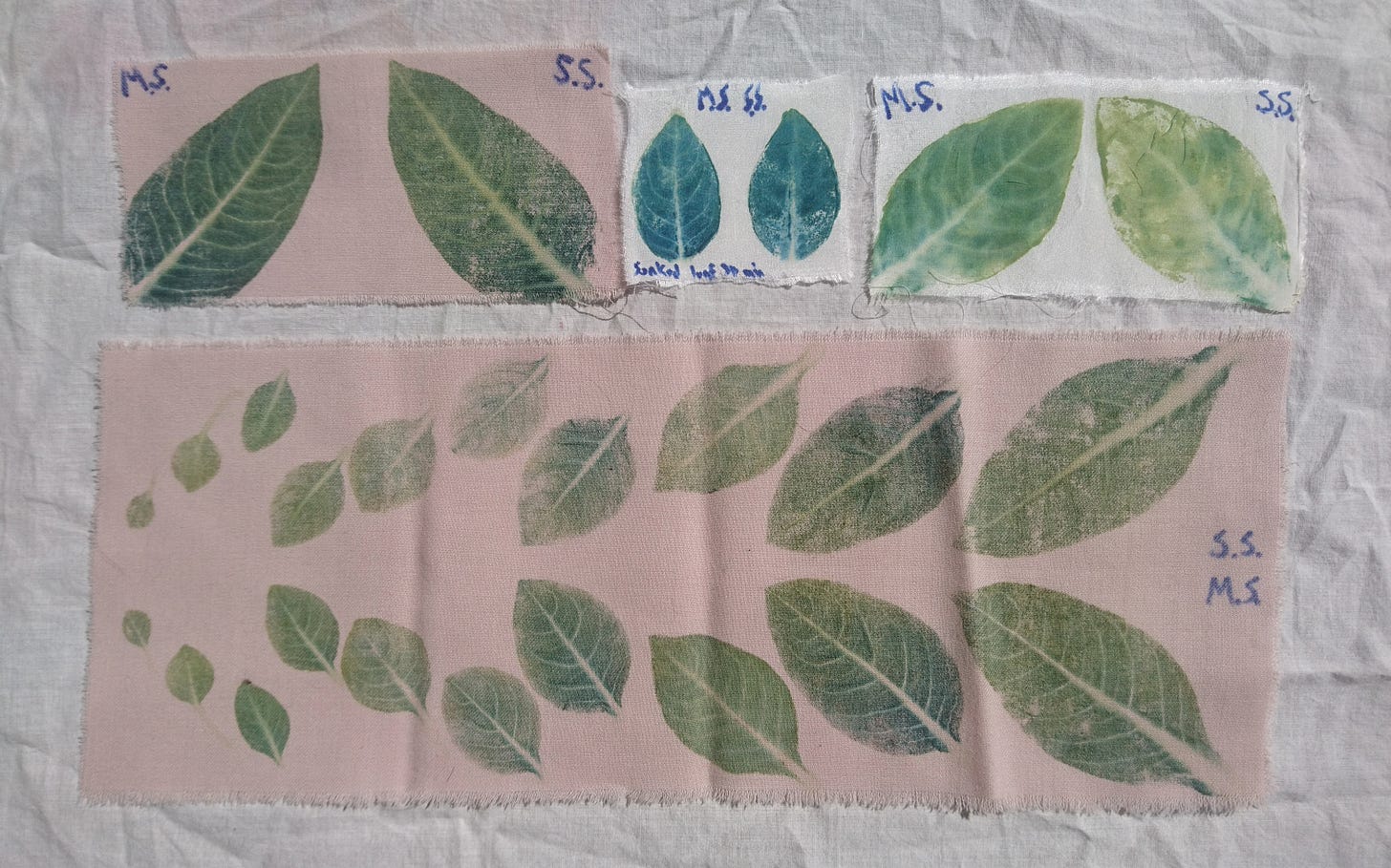

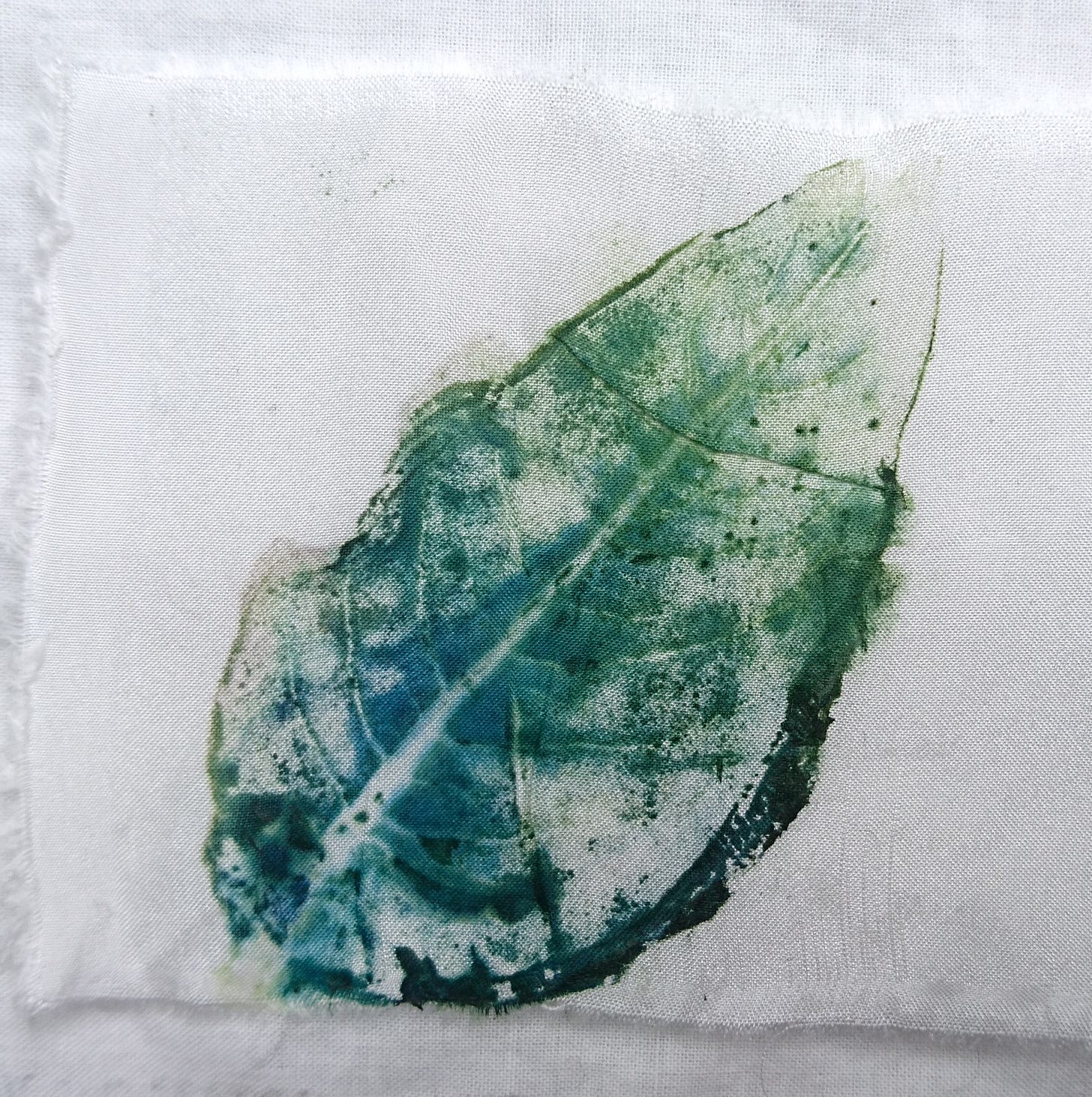

Hapazome is the art of “flower pounding,” and is most commonly used to impress flower and leaf imagery into cloth (this is not a direct translation of the word hapazome). This is fugitive, but when indigo leaves are used it is permanent. The indican in the leaves is squished into the cloth with a rubber mallet, combining with oxygen to leave green chlorophyll and indigotin behind. Work on a flat, smooth surface that is slightly porous. I prefer to have a pressing cloth or ‘blanket’ on top to keep the leaves in place. This cloth will also one day become a work of art as it, too, will acquire some colour with each use. The chlorophyll will eventually fade, but the blue pigment will stay. Leaves can be arranged and overlap for an ever deeper blue hue. Colours start light, and the fidelity of the image can be modified by how damp or dry the cloth is.

If a dyer was properly prepared, indigo would be grown in a pot that could be easily transported to a workshop location (and was aesthetically pleasing). In this way, leaves can be plucked at their freshest and used immediately for hapazome. Unfortunately, flower pots are heavy.

Salt Rub Dying is as simple as it sounds. Leaves and salt are crushed together to free the indican. Then cloth is added to absorb the indican saturated fluids. It is removed, aired briefly, and often sent for a second dip in a new set of leaves. The leaves shrink like steamed spinach, so this process requires many many leaves. This is a fun process and works to dye hair, too, since there is little water involved.

When I started pondering this question I would recommend a Cold Fresh Leaf Bath. Graham Keenan covers it on his website, as well as other methods that we have discussed.3 It’s another deceptively simple process4. Use cold water on a 18-25*C day to shred freshly plucked leaves in a food processor. Some folks like to add a little vinegar, claiming that it slows down the oxidation process.5 The leaves can be filtered or dumped whole into a bucket; although the latter causes one to work more later. A bit of scoured cotton makes an excellent filter for the leaves. Keep the water cool as protein fibre cloth is dipped into the bath and allowed to rest. Like with an indigo vat, repeated short dips are advised for darker colours. Oxidize the cloth in fresh water between dips, and once done dry it swiftly on a line.

More than blue

The fresh leaves of Persicaria Tinctoria (Japanese indigo) has the opportunity to create what is called Indirubin, a reddish-purple hued pigment that will bind into silk fibre. There is not a lot of information on indirubin because it is a difficult to acquire pigment, is only available in plants, and emerges during the application process. A useful series of experiments is shown here with different pre-dye treatment methods for the cloth6. I found this yesterday so I haven’t tested anything from this page. There used to be a PDF from Indigobluefields, but it has been taken down. The closest that I have gotten to using Indirubin is accidentally making my scarf a gorgeous dark blue that promptly rinsed out.

Japanese indigo is a fantastic plant that can create many colours. John Marshall has a class on Japanese indigo’s potential, which I believe includes indirubin.

In the end

We’re now in the season that is past the ideal temperatures for Hapazome or Salt Rub Dying. It’s too warm and the indican content will continue to decrease as the plants divert energy to create tiny blooms and seeds. The plants could be cut back over and over again, but indigo is very insistent on growing blooms when they believe that it is time for flowers. A Cold Fresh Leaf Bath might work, although it requires that the leaves are used swiftly after harvesting. It’s tough to be timely in the chaos of a kids summer camp.

I would recommend experimenting with a reduction vat. It can be used with scoured cotton t-shirts that kids bring to camp. The first test can be completed in a week from today. This gives enough time to move the fermentation into a larger jar, and another week to feed it delicious food stuffs while learning about your new vat. Consider the 1L jar as a sourdough starter and test it with small pieces of cloth. Start with a 1 litre pickle jar, washed thoroughly and left with hot water in it overnight. Empty this and refill the jar with the required amount of rain water. The water should be chlorine free, because chlorine inhibits the growth of bacteria. Use the small jar to cultivate the bacteria that you need. After this jar has had time to build up a good colony of bacteria it can feed

To maintain the warmth prepare a larger vessel with water that is the appropriate temperature, and immerse the jar 3/4 of the way up the side of it, but not higher than 1cm below the jar’s water line. If it’s inside a steel pot this can be put on the stove on occasion to heat if the temperature drops, but a plastic bucket works, too. Since we don’t need oxygen in this solution it could be covered with the lid.

Don’t forget to convert everything into the metric! Also break it down into the Xg per 100mL of water, as if it is a glaze recipe.

According to Cheryl Kolander of Aurora Silks you need;

Indigo - in your leaves!

Madder - Ah. Good luck. Catherine Ellis says that “My most recent experiments (c2022) have used both Dock root and Rhubarb root successfully. Madder, Dock and Rhubarb are all roots, all anthraquinones…..” For this vat you’re after the starches and sugars in the dyestuff, not the madder pigment, so some fresh finely chopped roots might do it.

Wheat Bran - available in the grocery stores, usually near the oatmeal.

Soda Ash - Can be purchased from Maiwa (I’d advise picking up madder, fructose, and indigo powder, too, if you believe that you’ll fall in love with indigo vats). Do not buy the ‘washing soda’ in the grocery store because it has bubble making ingredients in it.

Water - Somebody ought to have a rain barrel around, or a Berkey Filter.

During the camp, be sure to have a container of vinegar nearby. Some should be diluted in a bucket of water for both the cloth to be rinsed in after dying, and for kids to use if they get any indigo on them. Perhaps making them wear safety glasses is a good idea. A pH 11 solution in the eyeballs is no joke.

I’ve even got some used madder root that you can use to kick start your fermentation vat.

Good luck, dear Salamander!

So I ran the numbers for fun. In 1 litre of fermentation vat you need…

11.75 grams Indigo Powder (ergo, oodles of chopped up leaves)

4.99 grams used ground Madder (Rubia Tinctoria or Rubia Cordifolia)

4.99 grams Wheat Bran (is very light, so this will be a 1/2 cup to 1 cup in volume)

29.97 grams Soda Ash

1000.5mL 37-44*C warm rain water or chlorine filtered water

I’ve done some work fermenting liquids before. Looking at these proportions, I’d want to experiment with using twice as much Madder and Wheat Bran in the ‘starter’ jar to build up the bacteria faster. The indigo could be doubled, too. I would also heat the Wheat Bran gently to about 50*C for 15 minutes to get the bacteria groovin’ and break down some starches. Both the bacteria and the sugars/starches (bacteria food) are in both materials that and the madder, so add the madder, too. Allow it to cool to a reasonable temperature (or cool it with more water until it is 1L in volume) 27-32*C, and add the remaining materials. For scientific purposes both of these changes should be tested separately in different jars.

I’m not sure why the soda ash is added at the same time as everything else. I don’t think that bacteria likes pH 11.

Further reading

Maiwa has a lot of information about indigo, including a free documentary on the history of indigo and the Indian style of Indigo production,7 and classes.8 This PDF has an excellent summary of different vats.9

Graham Keegan has a free book from 1892 called Indigo Manufacture : Practical Guide with Experiments by J. Bridges-Lee M.A., and Indigo: From seed to Dye by Dorothy Miller10 Any of these books from his shop will deeply further your knowledge about their topic.

Also view all of the links in the footnotes. Many are duplicates from the clickable hyperlinks, but I like to have the full URLs posted, too.

https://www.digitsandthreads.ca/an-adventure-with-fresh-leaf-indigo-dyeing/

https://blog.ellistextiles.com/2020/01/30/indigo-still-learning-and-at-last-indigo-fermentation/

https://aurorasilk.com/wp/2019/01/01/indigo-natural-fermentation-vat/

www.youtube.com/watch?v=JgR7Q8EBbLU

https://www.grahamkeegan.com/i-grew-some-indigo-now-what

Good videos on fresh leaf dying! www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zbe5vCsR4pQ www.youtube.com/watch?v=hFGqnyexK1k

https://web.archive.org/web/20160329235713/http://www.lustauffarben.de/faerben-faerberknoeterich-englisch.html

http://www.wildcolours.co.uk/html/j_indigo_dye.html

https://www.mukogawa-u.ac.jp/~ushida/e_purple.htm

https://blog.ellistextiles.com/2021/11/07/the-surprise-of-indirubin/

I also just found this one https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280681709_Indirubin_the_Red_Shade_of_Indigo

https://maiwa.teachable.com/p/world-of-blue

https://maiwa.teachable.com/p/journey-into-indigo-se2023

Read this http://box19.ca/maiwa/pdf/indigo_data.pdf

https://www.grahamkeegan.com/shop/p/indigo-manufacture-book

https://www.grahamkeegan.com/shop/p/indigo-from-seed-to-dye-by-dorothy-miller

https://www.grahamkeegan.com/shop/books

I have found the link to Lust Auf Farben's english website, instead of the Wayback machine link.

English site: https://vergangen.lustauffarben.de/faerben-stricken-english-linkliste.html

Article on dying Japanese Indigo: https://vergangen.lustauffarben.de/faerben-faerberknoeterich-englisch.html